Pride and Spirit of Bedford Day

Thursday, July 17th, the Bedford Boys Tribute Center, under the direction of the founders and curators Ken and Linda Parker, will mark the 6th annual Pride and Spirit of Bedford Day with a private ceremony for the families of the 38 Bedford Boys who went ashore in the first assault wave on Omaha Beach, Normandy, France, with Company A of the 116th Infantry Regiment on D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Each July 17th has been Pride and Spirit of Bedford Day since 2019, when then-Mayor Steve Rush issued a proclamation designating the Day. It’s the anniversary of the day the telegrams, that left the town in shock, began coming in.

D-Day came and went. It was a momentous day and a great Allied victory; but, to a painful extent, the townspeople of Bedford were in the dark. They knew that the invasion had been successful, and they were battling the Germans inland. They were hearing news on the radio and reading news stories in newspapers, but what about their sons, brothers, and husbands?

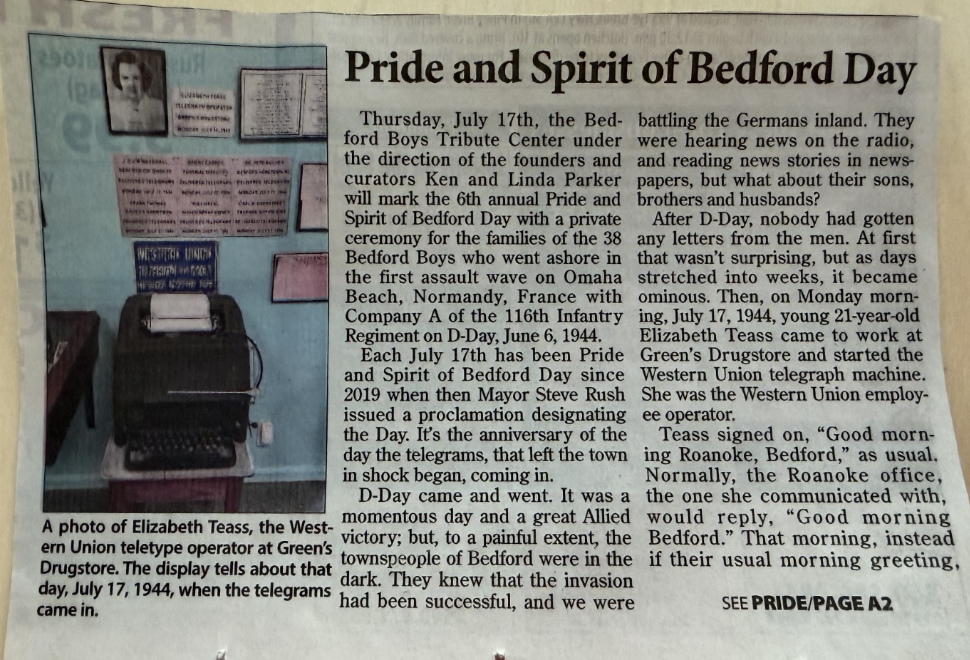

A photo of Elizabeth Teass, the Western Union teletype operator at Green’s Drugstore. The display tells about that day, July 17, 1944, when the telegrams came in.

After D-Day, nobody had gotten any letters from the men. At first, that wasn’t surprising, but as days stretched into weeks, it became ominous. Then, on Monday morning, July 17, 1944, young 21-year-old Elizabeth Teass came to work at Green’s Drugstore and started the Western Union telegraph machine. She was the Western Union employee operator.

Teass signed on, “Good morning, Roanoke, Bedford,” as usual. Normally, the Roanoke office, the one she communicated with, would reply, “Good morning, Bedford.” That morning, instead of their usual morning greeting, Roanoke replied, “We have casualties.” Then the telegrams started coming in, so many that the normal delivery driver couldn't handle them and others, including the sheriff, the local funeral director, a family doctor, and the local taxi-cab company owner, stepped in to help make deliveries.

Not all of these telegrams reported that a Bedford Boy had been killed. Many listed the man missing in action first. The telegrams confirming a death came days later. American military graves registration units were meticulous and didn’t list a man killed in action unless they were positive. However, in this case, it prolonged the agony as the final killed-in-action telegrams dribbled in over the next several weeks.

The town of Bedford went into shock. Miss Teass described Bedford of her day as a town where “Everybody knew yesterday what you were going to do tomorrow.” As a 1941 Bedford High School graduate, she had gone to high school with many of the Bedford Boys and certainly knew most of the men's families. She appeared to have never gotten over the shock of that day for the rest of her life.

The Pride and Spirit of Bedford comes from the way the town rallied around the grieving families of those men. The Rev. Dr. John Hunter Grey, pastor of Bedford Presbyterian Church, opened the church to serve as a refuge for farm families who had to come into town to await telegram news.

Ken Parker said that this annual anniversary commemoration is not to recognize July 17th as a day of sorrow and grief, but to be a reminder of how the people of Bedford came together to help their fellow townspeople during their darkest hour. This history of community pride and community spirit cannot be forgotten.

Women of the church cooked meals for these rural families and men of the church went out and worked their farms while the families waited. These families lived in the church for a week and a half awaiting telegram news.